Eluid Martinez is a longtime water management professional who served as the state engineer of New Mexico from 1990 to 1994 and the commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation from 1995 to 2000. Over his half-century in the world of water, Commissioner Martinez has witnessed the shift in the mission of state and federal water agencies from large-scale water development and construction to water resources management and technical support. He has also seen how the rise of the environmental movement altered the concept of water conservation from maximum beneficial use of all available resources to a broader focus on the public good. In this wide-ranging interview, Mr. Martinez tells us about his experience and provides useful advice for policymakers and for young water professionals.

Hydro Leader: Please tell us about your background and how you originally became an engineer and a specialist in water resource planning.

Commissioner Martinez: I went to school at New Mexico State University in the early 1960s and earned a degree in civil engineering. I was part of a co-op program with the New Mexico Highway Department in which engineering students would work 6 months of the year and go to school 6 months of the year. Upon graduation, the New Mexico Highway Department would employ us as junior engineers. After I graduated in 1968, I worked briefly for the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads in Northern California. Then, I came back to New Mexico to work with the Highway Department.

In 1971, I was hired by Steven Reynolds, who was then serving as the New Mexico state engineer and who ultimately spent 35 years in that role. As in most Western states, the New Mexico state engineer is the chief water official in the state and is responsible for the administration of water rights and permitting. State engineers are appointed by the governor and confirmed by the state senate. Shortly after going to work in the state engineer’s office as a young junior engineer, I became registered as both a professional engineer and a land surveyor in the state of New Mexico. During my tenure in the state engineer’s office, I helped the hydrographic survey section, which basically does the surveying and progression reports for the adjudication of water rights within the state. I worked in that position until 1984, when I was appointed by the state engineer as chief of the technical division, in which position I oversaw the hydrographic surveys section, the land use and water use section, the groundwater section, and the dam safety section. From 1984 through early 1990, I also served as a chief hearing examiner for the state engineer on protested water right applications.

In 1990, State Engineer Reynolds passed away, and there was a nationwide search for a replacement. I was selected by the incoming governor, was appointed the state engineer of New Mexico in December 1990, and served in that capacity through the end of 1994. As the state engineer, I was responsible for the administration of water rights in the state of New Mexico. I also served as a compact commissioner on the Rio Grande Compact and other compacts between New Mexico and adjacent states with respect to rivers flowing through New Mexico into other states. I also served as the chief administrative officer and secretary of the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission and served on the New Mexico Water Quality Control Commission and other commissions. In 1994, a new governor was elected. The governor was of a different political party than I am, and in January 1995, he replaced me.

Around February 1995, I received a call from the White House, asking me if I’d be interested in a position in Washington, DC. In March or April 1995, President Clinton nominated me as the new commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation. I was confirmed in December 1995 and served in that position until the end of President Clinton’s second term. After leaving Washington, I returned to New Mexico and opened a consulting company. Today, I still consult on water rights administration matters in the state of New Mexico.

Hydro Leader: What were the top issues you dealt with during your career in New Mexico prior to your appointment as commissioner of Reclamation?

Commissioner Martinez: The New Mexico State Engineer, like similar offices in other western states, was initially responsible for the development of the state’s water resources. I suppose the term originates in the era of building dams, water transmission systems, and so forth— developing the state’s water resources. Shortly before I became the state engineer, there developed across the American West a focus on conserving water. Concerns arose that a lot of streams, ecosystems, and fisheries had been damaged. The development phase came to a close across the American West. By the time I became the state engineer in 1990, there had also been a shift in the administration of water rights. In the early development period, water permits were granted to put water to its maximum beneficial use, but in the 1980s and 1990s, the concept of using water wisely for conservation and public welfare began to predominate. In the old days, conservation meant putting the maximum amount of water to the maximum beneficial use. That attitude changed toward one of using water not only to drive a state’s economy, but to carefully conserve it for other purposes and uses. When I became the state engineer, I had to deal with the fact that state laws had changed and that in approving water right applications or applications for changes or new uses of water, I not only had to look at the impairment of existing water uses and whether water was available but also whether the granting of the permit would be in the public welfare and whether it would impede conservation. Those are the issues that I was dealing with in New Mexico during the early 1990s, and they are issues that are still being dealt with today across the American West.

Hydro Leader: Aside from the dam safety work you alluded to earlier, did you do any other dam- and hydropower-focused work at that time?

Commissioner Martinez: Not really. The state engineer’s office dealt with the inspection and monitoring of private dams, but it didn’t have any jurisdiction over federal dams. During my tenure as the state engineer, no major dams were constructed, though there probably was some rehabilitation work done on a couple of minor structures.

Hydro Leader: When you moved to Washington, DC, to become the commissioner of Reclamation, what were the biggest changes in the work you were doing and the issues you were dealing with?

Commissioner Martinez: The history of Reclamation mirrors the history of water agencies across the West, since it began as a development agency that constructed dams, large structures, and projects and later became a water management agency. The development era came to an end at the time of the environmental movement, which opposed the construction of large new structures that would impede the flow of western rivers. When President Clinton was elected, he appointed a commissioner by the name of Daniel Beard. Dan came in with the agenda of transforming Reclamation from an engineering-oriented construction agency to a water management agency, and there was something of a backlash. Water users and managers across the West felt that the federal government should not be deciding how water was used, by whom, and in what quantities; they felt that that should be the remit of state governments and agencies.

After 2 years, President Clinton appointed me, a state engineer from the West, to take over. I started to rebuild the technical capability of the agency but shifted our focus from construction to the technical support of our projects, our infrastructure, and irrigation districts and projects across the American West. It was a period of transition.

During that era, I testified before Congress more than 40 times on water-related issues. One of the issues that arose at that time because of the environmental movement was the proposed removal of dams across the American West, including Glen Canyon Dam. I recall representing the administration at a hearing in a Senate committee on the removal of Glen Canyon Dam. I basically testified that I thought it was unrealistic. It is interesting that now, 25–30 years later, because of the drought conditions across the West, there are discussions about building dams and reservoirs again. We have gone full circle.

Hydro Leader: What other hydropower-focused issues did you work on during your time as commissioner?

Commissioner Martinez: At that time, most of the reservoirs in the West were full of water. Any hydropower issues that arose had to do with maintaining facilities to make sure that they continued to operate as they were expected to. Today, the lack of water in the rivers and reservoirs is drastically affecting their hydropower generating capability, so it’s completely different. I still remember going to Hoover Dam when Reclamation employees were opening the spillway tubes to flush water out of the reservoir. Today, they’re hoping that it rains enough to keep Lake Mead from hitting deadpool.

Hydro Leader: Looking over the decades of your career, what were the biggest trends or changes that you’ve seen?

Commissioner Martinez: Water officials across the West and in Reclamation are now having to deal with drought and shortage conditions that I didn’t have to deal with. When I first became the state engineer of New Mexico, I was in my mid-40s. New Mexico had an aggressive water rights administration management agency. I remember going to a meeting of western engineers in Las Vegas when I’d only been the state engineer for a few months. At that meeting, I said that New Mexico was actively looking at water conservation and trying to make a limited resource go as far as it could. Off the cuff, I made the comment, “When I was driving from the airport to this meeting, I noticed that all along the roads there were sprinklers irrigating grass in the middle of the day.” That drew an interesting comment from the water officials from Nevada. They said, “What we do here in Las Vegas is none of your business.” By the end of my term as commissioner, the Las Vegas Water Authority had undertaken an aggressive water conservation program, and it is doing a good job. I relate the story to demonstrate how things change.

Hydro Leader: Looking over the course of your career, do you have any advice for Congress or state legislators as they create water policy?

Commissioner Martinez: I’ve been involved in water issues now for almost 46 years. I’ve seen a lot of issues arise and go away and come back. In New Mexico, the question has cropped up every now and then of whether water management officials should be engineers. Keep in mind that these positions—state engineer and commissioner of Reclamation—were originally created as engineering positions because they were in the business of building and constructing projects. In New Mexico, there have been attempts to open the position of state engineer to individuals who do not necessarily have a degree and experience in water development and management. However, there is an immense value to practical experience. It’s easy to say, “This is the way things should be done”; it’s more difficult to actively manage a situation. I would advise those decisionmakers to listen to those who have had experience in dealing with the issues, not in hypothesizing about how the issues should be resolved. The problem today is that there are few of those individuals still around. I dealt with those issues to a certain extent 25 years ago, and I’ve seen what has occurred since then. Sometimes I feel like interjecting my views, but I don’t. I’m never asked, though, “Mr. Martinez, what would you do or what do you think?” It’s difficult for me to second-guess anybody else, but I would encourage today’s policymakers to reach out to those of the past so that they don’t reinvent the wheel.

At the age of 45, I became the first Hispanic state engineer in the United States, and unless I’m mistaken, there has not been another Hispanic state engineer appointed in the United States since 1990. I was also the first Hispanic commissioner of Reclamation in its 100‑year history. I raise the point because sometimes people from different backgrounds can bring different perspectives to the table that are good for the whole. I don’t subscribe to appointing individuals because of their ethnic background, but I do subscribe argument that if you can reach out to well-qualified ethnic minorities for positions, you should do so, because it brings alternate perspectives to the table.

Hydro Leader: Do you have any advice for water professionals who are at the beginning of their careers?

Commissioner Martinez: As you go into an agency or a firm, try to find and attach yourself to somebody whom you feel comfortable with as a mentor. I had that opportunity with Mr. Reynolds, and I learned a lot from him, not only from his advice but from observing how he acted and how he dealt with issues. A young professional coming into the area of water resources management or development has been trained in the technical aspects of the work but not in the human resources or management application of it. That technical background must be molded by your experiences. Learn from how your mentor makes decisions and presents themself. I was trained as an engineer, but I stopped doing engineering design and so forth early in my career. I became a manager of people and agencies, which is completely different.

My other piece of advice to an engineer or a water resource manager is to do what’s in the best interest of the public, the state, and the country. Leave your personal agendas behind. I found in state and federal government that there were individuals who tried to impose their own personal feelings or agendas on public policy. When I was the state engineer and the commissioner, I was concerned to ensure that my employees were not inserting their personal agendas into the organization’s decisionmaking process.

Hydro Leader: Would you tell us about your personal artistic pursuits?

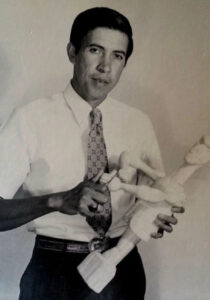

Commissioner Martinez: I was born in Cordova, a little Spanish-American village in northern New Mexico where people irrigate small acreages with acequias. My family has been there since the early 1700s. My mother’s side of the family are folk artists, carvers of religious imagery called santos. My grandfather and my uncle were famous woodcarvers. In the 1960s and 1970s, I began to carve, too, making me a fourth-generation woodcarver. This was before I had become the state engineer or commissioner. By the 1980s, I had developed a reputation as a folk artist. Some of my art pieces have gone into museums. In the 1980s and 1990s, some of my pieces were acquired by the Smithsonian Museum of American History, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the New York American Folk Art Museum, and other museums across the West and across the United States. I also painted and did watercolors. I continued to do that through my tenure as the state engineer. Some of my work was displayed in galleries. There’s a prohibition on presidential appointees having any outside source of income, so when I was appointed commissioner of Reclamation, I took all my art pieces out of the galleries and I stopped producing art. Only in the last couple of years have I returned to my art, principally because I’ve tapered off my consulting business. I’m back doing my art and enjoying what I like.

Hydro Leader: If any of our readers are interested, are they able to see any of your art on a personal website?

Commissioner Martinez: Yes; my art can be seen at eluidlevimartinezart.com.

Eluid Martinez is the former commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation. He can be contacted at eluid2010@hotmail.com.