More and more, the drought in the Colorado basin is affecting the amount of power that can be generated at Glen Canyon Dam and other hydropower plants on the Colorado River. That situation could get worse as lake levels decline. Hydro Leader spoke with Nicholas Williams, the Bureau of Reclamation’s power manager for the Upper Colorado Basin Region, about future scenarios and what the agency is doing to ensure continued power generation.

Hydro Leader: Please tell us about your background and how you came to be in your current position.

Nicholas Williams: I am currently the manager of Reclamation’s Power Office for the Upper Colorado Basin Region, which is based in Salt Lake City, Utah. I have bachelor’s and master’s degrees in civil engineering. I began working for Reclamation in 2004. At that time, much of my work was focused on modeling efforts, particularly modeling Lake Powell and Glen Canyon Dam for water quality and related programs. Later, I worked as regional liaison to Reclamation’s Washington, DC, office. Then I returned to Salt Lake City as the deputy power manager, and in 2020, I was promoted to the power manager position.

Hydro Leader: Would you talk about the hydropower facilities you oversee?

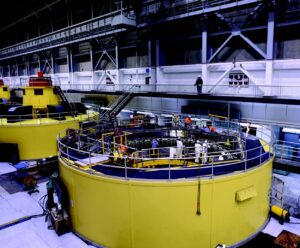

Nicholas Williams: Reclamation is the second-largest producer of renewable hydroelectric power in the United States. The agency generates an average of 40 billion kilowatt-hours of energy annually. That accounts for 15 percent of U.S. hydropower capacity and generation, equivalent to the demand of 3.8 million households. I am in the upper Colorado basin, but the entire Colorado River basin spans seven states—Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming—as well as part of Mexico. Within the basin, Reclamation owns and operates 12 hydropower plants. I oversee eight of those: Glen Canyon in Arizona; Flaming Gorge in Utah; Fontenelle in Wyoming; and five in Colorado: Blue Mesa, Morrow Point, Crystal, Lower Molina, and Upper Molina. Those eight hydropower facilities have a total capacity of 1,788 megawatts. Glen Canyon, with a capacity of 1,320 megawatts, accounts for almost three-fourths of their total capacity.

Hydro Leader: What are some of the effects that the Colorado basin drought is having on Reclamation’s hydropower fleet?

Nicholas Williams: The drought has two primary effects on hydropower generation. The first is that it reduces the volume of water that we’re able to generate energy with. The second is that it reduces the depth of the water in the reservoirs. That depth of water is important because it creates the force, or in technical terms, the head, that drives the turbines for hydroelectricity generation. The deeper the water, the more force we have for generating power. With reduced reservoir levels, we have less force. To date, in the upper Colorado River basin, the fluctuation in water volume has been the primary issue. Under some of our operating guidelines, in the future we will be releasing less water, which in turn will mean less generation. In water year 2022, which began on October 1, 2021, we are delivering 7.48 million acre-feet. In past years, our releases have been 8.23 million or even 9 million acre-feet. Water year 2022 will be a low year for generation, not only because of the lower reservoir elevation but also because we’re releasing less water.

Hydro Leader: To what degree is the drought already affecting the amount of power being generated? How might a continued drought affect power generation?

Nicholas Williams: The drought has reduced Reclamation’s entire Colorado River basin energy by 13 percent. We see that decline when we compare the 1988–1999 average annual energy production to the 2000–2020 average during the last 21 years of drought. Going forward, we anticipate an additional 16 percent decrease in energy generation for the years 2021–2023—in total, a roughly 30 percent drop from predrought conditions. We anticipate that that trend will continue. The two facilities that generate the majority of power for the entire basin are Glen Canyon, which I oversee, and its counterpart downstream, Hoover Dam. Those two facilities are at less than half capacity for reservoir storage, and it’s going to take a long time to fill them up. Going forward, at least until we start to fill them up, we will see less water released, which will affect generation.

Hydro Leader: Given that Glen Canyon Dam is a critical piece of Reclamation’s hydropower fleet, would you discuss the effects on that dam in particular?

Nicholas Williams: As of February 22, 2022, Lake Powell’s elevation was 3,527.98 feet above sea level. The minimum power pool elevation in Lake Powell at Glen Canyon Dam is 3,490 feet. We’re less than 40 feet above that critical, red-line elevation. Our February 2022 5-year projections show that Lake Powell has a 23 percent chance of dropping below minimum power pool in 2023. We expect to generate power until we reached that minimum power pool elevation. If we drop below that elevation, we would be unable to generate power, though water would continue to be released. Deadpool is the elevation below which we can no longer release water from Lake Powell. That elevation is 3,370 feet—120 feet below minimum power pool.

As winter wraps up and spring runoff starts, we continue to carefully monitor hydrology and its projected effects on Lake Powell’s elevation to help guide our operational decisions. Reclamation is doing all we can to plan ahead to protect what we have for the communities that depend on us for water and hydropower.

Hydro Leader: Is the minimum power pool elevation the level of the turbines, or is it the level at which you would no longer have sufficient head to generate electricity?

Nicholas Williams: It’s the level at which we would no longer have sufficient submergence on the intake to the power plant. The submergence level we need is about 20 feet above the intakes. Below that, the water starts to form a vortex that can be damaging to the power generation equipment.

Hydro Leader: What effects would reduced hydropower generation have on utilities and power customers?

Nicholas Williams: We’re already seeing some of those negative effects. Our power is marketed through the Western Area Power Administration, specifically its Colorado River Storage Project Management Center. That is the agency that markets and holds contracts with the municipalities, utilities, cooperatives, and tribes that receive our power. It markets the power under a rate, and that rate increased by 11 percent in December 2021, largely because of the longevity of the drought. We had a stable rate through most of the drought up to this point, but now, with storage at the current levels and decreasing water volumes, the rate is being affected. We will have this higher rate for approximately 2 years. Beyond that, it will be determined by conditions and our projected generation at that time. The energy demand doesn’t go down, just our ability to supply that energy, so it has to be supplied from other sources. That has the potential to affect customers as well. Other sources might be more expensive or might put more strain on the entire grid.

Hydro Leader: What would be the effects on the grid in terms of power supply and ancillary services like black start?

Nicholas Williams: Hydropower provides firm power but also grid support services to support the transmission of that electricity in a safe, reliable manner. As the drought continues, those support services will continue to be affected. Glen Canyon does provide a black start resource. If we fall below minimum power pool, we will lose the ability to provide that support. I can’t really speak to the broader effects on the grid, but the drought will affect our ability to provide some of those services.

Hydro Leader: What is the best way to balance power generation and water supply for agricultural, residential, and industrial uses?

Nicholas Williams: That’s a difficult question to answer. Reclamation must also factor in things like mitigating adverse impacts and protecting downstream natural, recreational, and cultural resources. We’re governed by what’s known as the Law of the River, a collection of agreements, compacts, and federal laws that govern the release and use of water on the Colorado River. Energy, agriculture, municipal, and environmental needs fluctuate, so we work closely with stakeholders to understand what the needs are and try to achieve that balance. That balancing act is happening in collaboration with stakeholders and will continue to happen on the Colorado River in a variety of different forms and settings.

Hydro Leader: How is Reclamation working to ensure continued power generation at Colorado basin dams, including Glen Canyon?

Nicholas Williams: There are several different approaches that we’re working on to protect the critical elevations of Lake Powell, particularly the target elevation of 3,525 feet, which provides a 35‑foot buffer above the minimum power pool elevation of 3,490 feet.

We’ve made changes to increase the efficiency of our power plants and continue to look for additional opportunities to make improvements. For example, at Glen Canyon Dam, from 2007 to 2015, we replaced all the turbine runners, which resulted in efficiency gains of more than 3 percent.

We are also exploring the feasibility of modifications to Glen Canyon Dam to allow it to produce power below the current minimum power pool elevation, perhaps as close as we can get to deadpool elevation. We are early in that process, but we’re entering studies to look at what we can do to ensure we can continue to generate power at Glen Canyon on all water that is released to meet obligations under the Colorado River Compact. Reclamation, the Colorado River basin states, tribes, stakeholders, partners, and the public are monitoring the situation on the Colorado River. We’re engaged together to protect the elevations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead. That remains a top priority going forward.

Hydro Leader: Do you expect major changes in water use and power generation going forward?

Nicholas Williams: We’re seeing major changes in climate and changes in water and electricity use. I’d expect that we will continue to see changes in the policies that govern those uses. As for our facilities, hydropower is a small part of that energy generation portfolio, but I’d say it’s an important part. Hydropower punches above its weight class not just in terms of providing energy but in all the services it provides. In the West, where our facilities are, we have a highly variable and limited water supply. There will continue to be changes, and we need to be able to adapt to them.

Nicholas Williams is manager of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Power Office for the Upper Colorado Basin Region. He can be contacted at nwilliams@usbr.gov.