Intake Screens Inc. (ISI) was founded in 1996 to manufacture industrial-grade fish protection and debris management screen systems. Today, it designs custom screens for hydro, irrigation, municipal, and industrial facilities around the world. In this interview, ISI President Russell Berry IV and Director of Technical Services John Burnett tell us about the company’s history and its services for hydro facilities.

Hydro Leader: Please tell us about your backgrounds and how you came to be in your current positions.

Russell Berry: I grew up working with my dad, who pioneered and patented new screen designs over a decades-long professional career. Starting when I was very young, I went out with my dad and installed screen projects on the weekends. When I was about 18 or 19, I actually started getting paid to work. In those early years, I did the welding, fabrication, and installation work; after gaining some years of experience, I started doing some of the design work as well. Soon after that, I got involved in hiring employees; keeping them lined out every day; and doing all the design, manufacturing, and installation of our screen systems. In 2008, my dad stepped back, and I was named president of the corporation. For the last 5 years, I’ve been responsible for all aspects of the business, from running meetings to signing contracts and sweeping the floor. In all seriousness, I do make sure that I still put on a wetsuit, run an excavator, and provide thoughtful input on designs, as it is the creation of quality industrial products that fulfills me most.

John Burnett: I’m a fishery biologist by training and hold a master’s degree in the subject. I spent 20 years consulting on various fish protection projects and leading small and large teams on biological sampling programs, intake technology feasibility and alternatives analyses, and economic evaluations. I helped clients make informed decisions about how to optimize fish protection and debris management at their water intakes. I came to know all available fish protection and debris management methods and screening options and came to value ISI’s technologies over all others in the marketplace. In fact, Russell and I developed some large projects together over the 10 years before I joined ISI. After leaving consulting and working for 2 years in the fish protection program at the Electric Power Research Institute, I decided to join ISI as a director on the project development side, and that’s where I sit today.

Hydro Leader: Please tell us more about the organization’s history, focus, and customer base.

Russell Berry: Starting in the 1970s, my dad worked on a ranch in Nebraska where center-pivot irrigation systems were being installed. The ranch was pumping out of a river, and he was getting leaves, pine needles, and other debris in his sprinkler head, so he made some self-cleaning screens to keep his pump and irrigation system operating. In 1980, he quit the ranch and started Plum Creek Manufacturing, a small company in Nebraska that produced self-cleaning screens for irrigation systems. He sold screens across the United States and even sold a few internationally. Ultimately, he sold Plum Creek Manufacturing in 1990, and our family moved to California.

The early 1990s was a period of increasing focus on fish protection screens because of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), state regulations, and the need to develop working screen systems for larger intakes. My father saw that the need for industrial screen applications at larger intakes could not be fulfilled with the technologies being used in irrigation. In 1996, he started ISI, with the sole purpose of designing a more industrial-grade screen system.

Today, we deliver screens across all industries that convey water: irrigation; municipal water; hydropower; thermal generation; and all types of industrial facilities, including an increasing number of desalination facilities. We have completed more than 300 custom screen design projects, some of which include 10 or even 20 screens. We have projects around the globe, including throughout the United States and in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Peru, and the UK. Fish protection requirements around the world are becoming increasingly stringent, and that’s creating an opportunity for us to deliver screens in even more applications and to become better at what we do.

Hydro Leader: What differentiates ISI fish and debris protection screens from other screens on the market?

Russell Berry: Facilities usually have a bar grate or some kind of trash rack to keep large debris from going into the intake. Any kind of finer filtration is done on the pump discharge. With fish protection, there’s a need to screen the water on the suction side, or inlet side, of the pump. There are regulatory criteria for the size of slot openings, which can go down to 1–2 millimeters (mm) and sometimes smaller, and for approach or through-screen velocity. We typically custom design our screens for the site conditions and these specific fish protection requirements.

The screens consist of wedge wire, which is triangle shaped and can be used to create a strong screen structure. We size the screens so that they have low approach and through-screen velocities. For cylindrical screens, we install a drive system—a submersible electric drive, a hydraulic drive, or a turbine drive—that rotates the screen against a fixed external brush. There’s also an internal brush that cleans the inside of the screen to prevent algae and fouling organisms, such as barnacles or mussels, from adhering and growing. The internal brush also does a great job of keeping sand or small rocks from getting pinned in the wedge-wire screen openings. Because the cleaning system is so effective, the screens don’t have to run all the time. They’ll typically be passive or stationary for 6 or 12 hours. Then, the screen will go through a cleaning routine: it will rotate the cylinders slowly against the brushes—1 minute of forward revolution and 1 minute in reverse—and then shut off. The fact that the screens are not running all the time is a key reason why we can put screens out in a lake or river and expect them to operate for 10–15 years with little maintenance.

Hydro Leader: Where are ISI screens typically installed at a hydro facility, and how are they operated?

John Burnett: Roughly 90 percent of our screens are installed in the source water body at the entrance to the facility. We design the screen system to have low approach and through-screen velocities, and they typically have the small slot size that Russell mentioned. That allows us to essentially eliminate potential effects on fish: The small slot size prevents fish from being drawn through the screen and into the facility, and the low velocities prevent fish from being trapped against the screen surface. The screens also keep debris and fish in the source water body with no collection or conveyance, as occurs with other screen systems. These elements are key to reducing potential effects on fish and preventing incidental take under the ESA. The best proof of our ability to minimize potential effects on fish is the hundreds of installations of our technology in designated critical habitat for ESA-protected species, including anadromous salmon and sturgeon.

Some hydro facilities have off-channel diversions and a fish bypass. These facilities use the same elements in designing the screen system that I just mentioned, but have a fish bypass downstream of the screen so that fish can be returned to the source water without being withdrawn into the turbine flow or impinged on the screens.

Our screens are operated using a control panel with a touchscreen human-machine interface. From that control panel, you can program the frequency and duration of screen cleaning to correspond to the conditions at a particular site. That control panel also receives information on the screens’ operational conditions—for example, whether they are rotating—and can receive signals from other onsite instrumentation—for example, a water level sensor system can dictate a screen cleaning cycle. The same control system can also be configured to open or close a knife gate or raise or lower the screens, if those features are part of the system. We can also customize a system to allow for the remote monitoring and control of the screen system. Design of the controls is typically a key point of engagement among ISI, the engineer of record, and the facility owner, and the system is optimized for the end user.

Hydro Leader: You alluded to different screen shapes and drive types. Which screens are typically used for hydro facilities?

John Burnett: Cone screens and cylindrical screens are the two key shapes we use to build screens. We’ve built flat-panel screens as well, but have found that the conical and cylindrical shapes almost universally result in smaller total project footprints and lower total project costs. Cylindrical screens can be fitted with an internal and external brush cleaning system, which is also a key advantage of that screen shape. For our hydropower projects, we’ve consistently used cylinder screens in both T-screen and drum-screen configurations.

The drive type is selected based on site conditions. At a hydro facility, we would typically recommend an electric drive to rotate the screen cylinder between the internal and external brushes. We take the submersible motor and couple it to a high-reduction gearbox to build our drive assembly, because we want our screens to rotate twice per minute—a low-speed, high-torque screen rotation. We use the electric drive assembly because it’s simple and robust. The motor inside the screen will typically be 1–2 horsepower, so operating the brush cleaning system consumes little power.

We’ll use a hydraulic-type drive on screens that might be operating in the mud, on the bottom of the river, or in locations with high siltation. Hydraulics are low-speed, high-torque systems that have more of a tendency to slip. Hydraulic drives can be stalled out, reversed, and often overcome a buried condition, which can happen on some high-bed-load, flood-prone rivers.

Our turbine drive is for sites that do not have any power available. It is basically a propeller inside the inlet. When water flows through the screen, it spins the propeller, which is coupled to a high-reduction gearbox that rotates the screen. We’re using the energy of the water going through the screen to operate the cleaning system.

Hydro Leader: What is the largest installation you have at a hydro facility?

Russell Berry: Our largest screen system is an irrigation diversion that diverts 1,450 cubic feet per second (cfs). There’s no reason why it couldn’t be applied at a hydro facility. Our largest hydro facility screen install is at a 550 cfs Pacific Gas & Electric structure on the Stanislaus River in California. At a large hydro facility, you might expect to have more than one screen—maybe two, five, or more.

John Burnett: Keep in mind that there’s a direct correlation between the flow rate and the size of the screen. For every cfs of screen flow, we typically have around 3 square feet of screen surface. For a 500 cfs intake, we’d have roughly 1,500 square feet or more of screen surface area. This is where the cylinder shape screens come into play and allow us to fit a lot of screen surface area in a small project footprint.

Hydro Leader: Do you have any interesting projects in the pipeline right now?

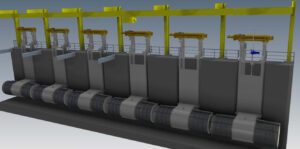

John Burnett: One interesting project we expect for next year is a deep-water pilot study in Europe in which we plan to deploy our electric drive screens in a lake at a depth of 60 meters, or about 200 feet, and evaluate their operational effectiveness and the water quality produced from a 0.5 mm slot opening. In terms of full-scale projects being built today, we are fabricating a large screen system with four T-screens and retrieval tracks that will be installed in the Hudson River. The screen system will have 0.75 mm slot openings and a 0.5‑foot-per-second through-screen velocity. The screen system is being installed to protect river herring, sturgeon, and other species in the Hudson River.

Hydro Leader: What is your company’s vision for the future?

Russell Berry: ISI has spent the last 25 years perfecting methods of designing and building screen equipment. Our objective as a company is to have engineering firms across the country reach out to us when they are involved in designing an intake structure, retrofitting an existing intake with fish screens, or complying with fish screen requirements. We want to be a trusted resource for sharing our experience and examples of what we’ve done before to address the various conditions and challenges that are encountered at intakes today.

Russell Berry is the president of Intake Screens Incorporated.

John Burnett is the director of technical services at Intake Screens Incorporated.

For more information about ISI screens and projects, visit www.isi-screens.com.